How Can Wild Animals Be Friends With Humans

Building healthy relationships between people and nature to benefit wild animals

Key takeaways

- The desire to build good for you homo-nature relationships is a goal that is shared by restoration ecology and wild animal welfare. Both disciplines incorporate environmental stewardship into the human-nature human relationship, yet they have subtle differences in how people orient their problem-solving behavior.

- Restoration ecology tin straight people to be reactive to harms to the surroundings. This orientation limits our ability to imagine ourselves equally a part of the solution to environmental issues.

- In contrast, wild animal welfare calls on people to act to meliorate wild fauna' lives. This proactive human-nature relationship empowers people to benefit wild animals, not simply exacerbate the issues they face.

- Urban wild animals diseases are an opportunity for wild animal welfare and restoration ecology to synergize. Whereas welfare biological science may focus on administering vaccines and medicine to benefit wild animals directly, ecological restoration could focus on urban planning and restoration to reverse the corporeality of impervious surface in cities. This combined arroyo addresses the problem of urban wildlife diseases on two fronts.

Summary

Information technology is crucial to bandage people every bit agile participants in ecosystems who tin can, and should, do more just exacerbate environmental issues. People need the opportunity to benefit the natural world and its inhabitants. The wild animal welfare ethic empowers people to have a positive bear on by defining a healthy homo-nature relationship in proactive terms.

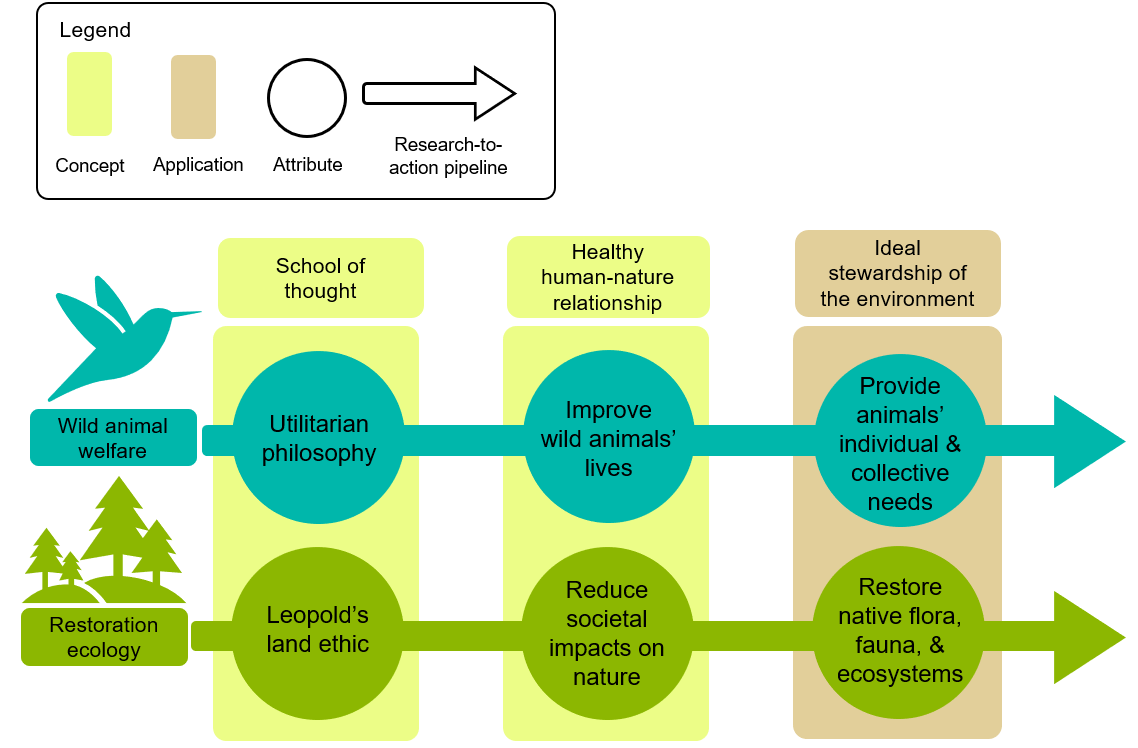

Assumptions about the man-nature relationship influence stewardship goals. A wild animate being welfare arroyo seeks to provide for animals' individual and collective needs. In restoration ecology, the goal is to restore native flora, creature, and ecosystems (Fig. 1). Each project has its strengths and weaknesses in terms of prioritizing long-term sustainability, maintaining ecosystem function and community biodiversity, being informed by the past and future, and engaging and benefiting club (Fig. 2, Table 1).

From a pragmatic point of view, restoration environmental and welfare biological science can and should course a productive union to solve complex wild fauna bug. Wild fauna diseases in urban environments are an instance of a transdisciplinary cause area. There are several mitigation techniques that are bachelor today, the most salient beingness providing medicine and reducing the impervious surface in the mural. Whereas providing wild animals with medicine is favored by the wild animal welfare community, restoration ecology has its own expertise in landscape planning and restoration. Combining these approaches reveals the potential synergy for addressing this trouble. Overall, mitigating diseases in urban environments tin can ameliorate the well-being of wild fauna, as well equally serve equally a larger case study as to how projects for animals' well-being tin complement traditional modes of environmental management.

Article

Both restoration ecology and wild animal welfare aim to build healthy relationships between humans and nature in order to inspire people to steward the natural world.ane, two What is a healthy human being-nature relationship? The concept is value-laden along 2 lines: the type of relationship between humans and nature and how to make the relationship healthy once it has formed.

The type of human-nature relationship that is advanced varies betwixt welfare biological science and restoration ecology. The divergence arises because the two disciplines have emerged from unlike schools of idea. The wild animal welfare move often draws upon utilitarian philosophy: doing as much good for as many sentient beings (man and nonhuman animals) as possible.three Restoration ecology is informed by Leopold's land ethic,iv which blends an intrinsic value of nature with the instrumental value of ecosystems to support nonhuman and human life. Information technology is worth noting that both disciplines contain pluralistic ideals5, six and that the utiliarian school of idea is besides not exclusive to animal welfare, as conservation as well uses consequentialism.vii Regardless, the dominant value systems usually advance subtly different roles for people innature (Fig. 1).

Effigy 1. Parallel ideas in wild animal welfare and restoration environmental.

Restoration ecology's goal of "reduc[ing] societal impacts on the natural world"viii implies a reactive human relationship betwixt people and nature, in which people react to environmental degradation and assistance render ecosystems to their natural function. One common restoration tool is the natural (or spontaneous) regeneration approach, in which the source of ecology degradation is removed and no additional interventions alter the recovery trajectory.eight The prescription has an ecological footing, as ecosystems do have a natural ability to recover and remain functioning. Yet, characterizing people's ideal role with nature in this manner, every bit just reactive to man-caused harm, limits our ability to exist helpful stewards of nature. This blindspot is elegantly described by the ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer, who surveyed her grade of advanced environmental-studies students:

"They were asked to rate their understanding of the negative interactions between humans and the environment. Virtually every ane of the two hundred students said confidently that humans and nature are a bad mix… Afterward in the survey, they were asked to rate their knowledge of positive interactions between people and state. The median response was 'none.' I was stunned. How is it possible that in 20 years of teaching they cannot think of any beneficial relationships betwixt people and the environment? …When we talked about this later on class, I realized that they could not even imagine what beneficial relations between their species and others might look like. How can we brainstorm to move toward ecological and cultural sustainability if we cannot even imagine what the path feels like?"ix

It is crucially of import to cast people as active participants in ecosystems then that people have the opportunity to benefit the natural world and its inhabitants. As active participants in ecosystems, people can and should imagine themselves as long-lasting solutions to a broad range of environmental bug. Infusing proactive qualities into human being-nature relationships is key to making these relationships healthy.9,ten Wild animal welfare is one such ethic that defines a man-nature relationship as good for you when information technology is proactive. The ethic of wild animal welfare asks people to act to improve wildlife' lives, not but exacerbate the problems they face. This telephone call to action empowers people to take a positive human relationship with wildlife past enhancing animals' quality of life.

Effigy 2. Relative strengths of ideal environmental stewardship projects in wild animal welfare (left) and restoration environmental (right). Adapted from Suding et al. (2015).

To improve the quality of life of a free-living animal, 1 ideal projection from the ethic of wild animal welfare is to provide for animals' individual and commonage needs.11 In contrast, the platonic example of ecology stewardship in restoration ecology is to restore native flora, fauna, and ecosystems.8 To illustrate the differences between these projects, I compared them using a set of four principles put frontwards in the restoration literature: 1) ecosystem office and community diverseness, 2) long-term sustainability, iii) informed by past and future, and iv) benefits and engages society.12 These four categories tin be used to articulate and outline the priorities and trade-offs that are generally important to consider in environmental stewardship projects. When viewed adjacent, we can begin to understand how wild animal welfare projects differ from traditional stewardship projects in conservation and restoration ecology, also as infer each subject area's relative strengths.

Table one. Explanation of relative strengths of ideal environmental stewardship projects in wild animal welfare and restoration environmental. Principles chosen following Suding et al. (2015).

No one subject can be expected to optimize every angle, especially for multidimensional ecology problems. From a pragmatic point of view, restoration environmental and welfare biology can and should class a productive matrimony to solve complex wild fauna bug. One transdisciplinary crusade-area is wildlife diseases in urban environments. Risk of disease is acute in urban environments because of four factors: urban-fauna customs dynamics, animal behavior, landscape patterns, and human activities.xiii

Man travel, for instance, introduces and spreads novel pathogens throughout the earth, and our addiction of keeping domestic pets exposes wildlife to illness. The human density in cities magnifies these negative effects. Dense homo habitation also alters the landscape pattern, every bit the transportation, infrastructure, and industrial sectors tend to increase in cities. This increment has two direct impacts. First, an increase in pollution and toxins to the environment. 2nd, landcover changes from living features to a potency of impervious surfaces (concrete structures).13

Because most species cannot accommodate to an environment dominated by concrete, an increase in impervious surface correlates with biotic homogenization—the loss of native biodiversity and a concomitant hyperabundance of a few well-adapted species, such as mice, rats, gray squirrels, starlings, and house sparrows. The behaviors of these animals, in turn, make them more susceptible to disease. These animals tend to alive communally and cluster around food resources, and and so transmit pathogens amid each other at an unusually high rate. Urban-adapted animals are too singular in their ability to habituate to people. As a consequence, they live in unusually-shut proximity to the novel pathogens and pollutants that are the byproducts of dense settlements and human activities.13

These affliction dynamics are complex, and at that place are several more factors at the landscape scale and the scale of the individual animals themselves that I do not describe here. Nevertheless, at that place are several mitigation techniques that are available today, and could exist made more accessible in the future: vaccines, other medicines, and mural planning, particularly reducing the spatial extent of impervious surfaces by planting beneficial vegetation and building parks or wildlife corridors.13 The most ethical and effective strategies to mitigate wildlife diseases accept yet to be determined. More piece of work is needed to evaluate how much they reduce affliction adventure in any particular context, as well as how these methods impact the well-being of individual animals and the net-welfare of an animal customs in the long term.

Each strategy listed is, at least, an expression of a healthy human-nature relationship in which people help wild fauna survive and thrive. The wild animal welfare community favors providing animals with vaccines or other medicines, whereas the restoration community looks to reverse biotic homogenization and restore natural landscape features. When approaches from the ethic of wild fauna welfare and restoration ecology are combined, the potential for synergy to accost environmental problems is revealed. Ultimately, mitigating diseases in urban environments can serve as a larger case written report as to how projects for animals' well-being can complement other types of ecology management, in add-on to simply improving the well-being of a vast number of wildlife.

References

- Dunn RR, Gavin MC, Sanchez MC, Solomon JN (2006) The dove paradox: dependence of global conservation on urban nature. Conservation Biological science 20:1814-1816

- Heberlein TA (2012) Navigating environmental attitudes. Oxford University Printing, New York, New York

- Singer P (2001) Practical ethics. Third edition. Cambridge University Press, New York, NewYork

- Leopold A (1966) The land ethic. Pages 237–264. In: A Sand County annual with essays on conservation from Round River. Oxford University Press, New York

- Fraser D (2008) Understanding animal welfare. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica fifty:S1 In: The part of the veterinarian in animal welfare. Animal welfare: too much or too little? The 21st Symposium of the Nordic Commission for Veterinary Scientific Cooperation (NKVet). 24-25 September 2007. Værløse, Kingdom of denmark

- Robinson JG (2011) Ethical pluralism, pragmatism, and sustainability in conservation practice. Biological Conservation 144:958-965

- Johnson PJ, Adams VM, Armstrong DP, Baker SE, Biggs D, Boitani 50, Cotterill A, Dale E, O'Donnell H, Douglas DJ, Droge E et al. (2019) Consequences affair: compassion in conservation means caring for individuals, populations, and species. Animals ix:1115

- Gann GD, McDonald T, Walder B, Aronson J, Nelson CR, Jonson J, et al. (2019) International principles and standards for the do of ecological restoration. Second edition. Restoration Environmental 27:S1–S46

- Kimmerer RW (2013) Braiding sweetgrass: indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge, and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions. Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA

- Allison SK (2007) Yous can't not choose: embracing the role of option in ecological restoration. Restoration Ecology 15:601-605

- Sebo J (2020) All we owe to animals. Aeon, xv January 2020 https://aeon.co/essays/we-deceit-stand up-by-as-animals-suffer-and-die-in-their-billions [Accessed three March 2020]

- Suding Thousand, Higgs E, Palmer M, Callicott JB, Anderson CB, Bakery M, Gutrich JJ, Hondula KL, LaFevor MC, Larson BMH, et al. (2015) Committing to ecological restoration. Science 348:638-640

- Bradley CA, Altizer S (2006) Urbanization and the ecology of wild animals diseases. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 22:95-102

Source: https://www.wildanimalinitiative.org/blog/peopleandnature

Posted by: hayesaltylets.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Can Wild Animals Be Friends With Humans"

Post a Comment